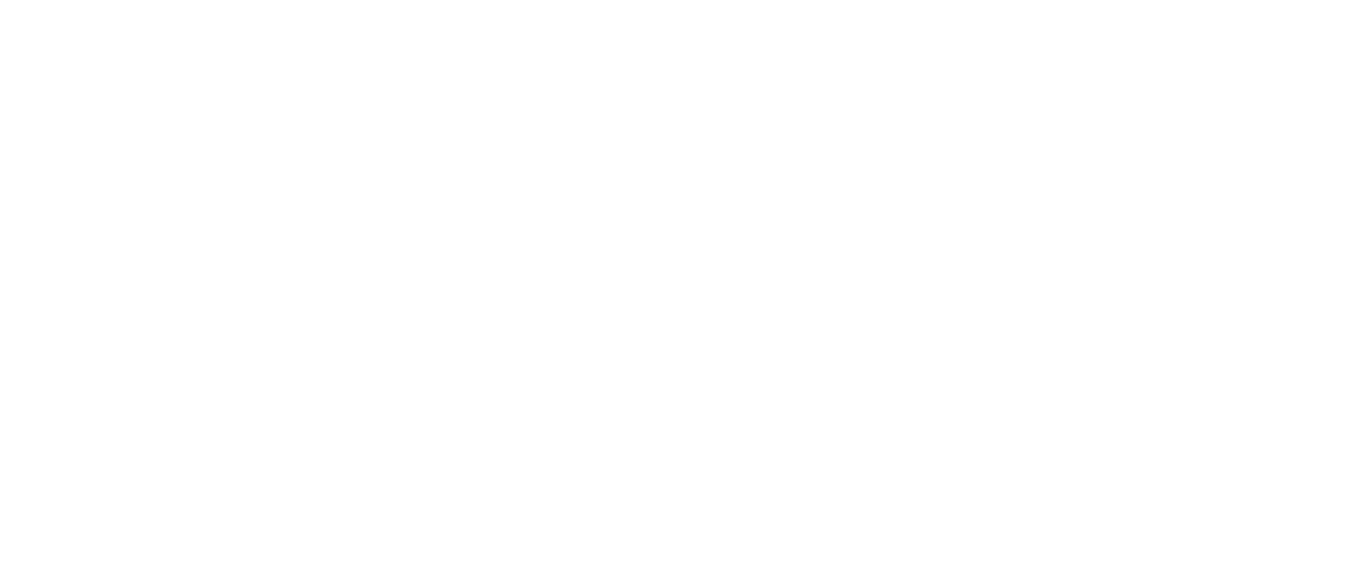

Ubley Hill Pot

A Tale of a Chance Discovery, a Hasty Dig, and a Chamber of Bones.

Discovery & Opening

Ubley Hill Pot was discovered in 1960 when Malcolm Cotter, Barry Ottevell, and Arthur Cox stumbled upon a large, deep shakehole that was invisible from just a few yards away. Although the initial inspection revealed no bedrock, its size was promising.

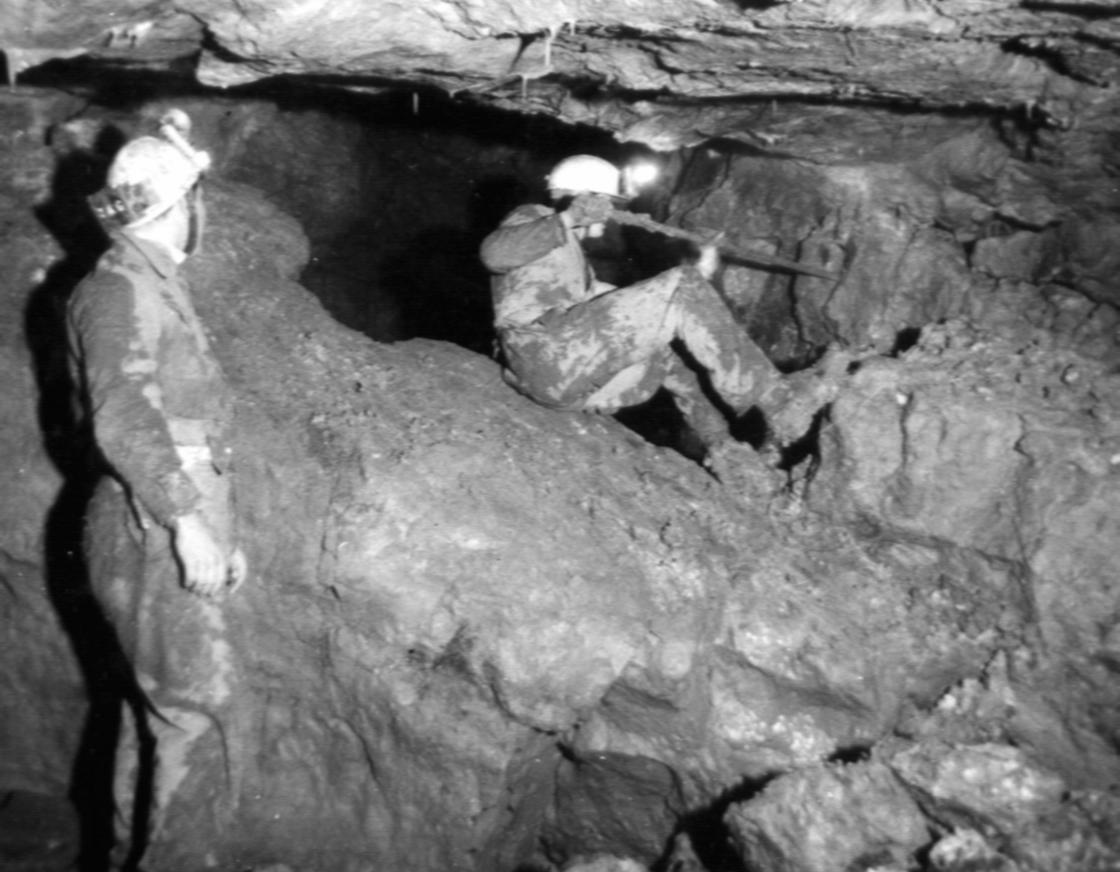

Action was spurred when another caving party was spotted in the area, and a dig was organized for the August Bank Holiday. After several test pits, the team focused on a promising spot and began removing water-worn boulders—a sign of past water action. The breakthrough came after shifting a large rock at a depth of five feet, revealing a small, tantalizing tube. As the dig progressed, the sound of falling rocks from below hinted at the space to come. Soon after, the team broke through a tight squeeze into the top of a large chamber, marking the opening of the cave.

Cave Description

The entrance to Ubley Hill Pot is down a Concrete Piped shaft, requiring a 20m ladder. This opens to a tight and awkward squeeze at the top of a rocky chamber. From here, a 10m pitch broken into 2 descends to the chamber floor. This is the cave’s most significant feature: the Bone Chamber.

This chamber was found to contain a vast and haphazard collection of human and animal remains, including human skulls (one of which was mistaken for a stalagmite), animal bones, and antlers. Further exploration revealed a tight section and a later extension, found by digging through a mud slope, which led to a high rift and a small waterfall. This final passage extended the cave’s total length to approximately 75m.

At a Glance

- Author: Malcolm Cotter

- Discovered: Mid-1960

- Location: Near Ubley Hill Farm

- Depth: 38 m

- Length: ~75 m

- Key Features: Tight entrance, two main pitches (20m & 10m), the Bone Chamber, and a final waterfall chamber.

- Notable Finds: Human skulls, extensive animal bones, antlers and a broken rope ladder.

On a fine day in mid 1960… [etc.] …The rock which had collapsed was part of the bedrock that had been dissolved away and undercut.